- THE CHOICE OF A WIFE

- THE CHOICE OF A HUSBAND

- CLANDESTINE MARRIAGE

- DUTIES OF HUSBANDS TO WIVES

- DUTIES OF WIVES TO HUSBANDS

- COSTUME AND MORALS

- HUSBANDS AND WIVES

- MATRIMONIAL DISCORDS

- HOTELS VERSUS HOMES

- EASY DIVORCE

- Maternity

- THE CHILDREN’S PATRIMONY

- THE MOTHER OF ALL

- SISTERLY INFLUENCE

- TRIALS OF HOUSEKEEPING

- WOMAN ENTHRONED

- THE OLD FOLKS’ VISIT

- THE DOMESTIC CIRCLE

"Go home to thy friends, and tell them how great things the Lord hath done for thee."—Mark 5:19.

There are a great many people longing for some grand sphere in which to serve God. They admire Luther at the Diet of Worms, and only wish that they had some such great opportunity in which to display their Christian prowess. They admire Paul making Felix tremble, and they only wish that they had some such grand occasion in which to preach righteousness, temperance, and judgment to come; all they want is only an opportunity to exhibit their Christian heroism. Now the evangelist comes to us, and he practically says: "I will show you a place where you can exhibit all that is grand, and beautiful, and glorious in Christian character, and that is the domestic circle."

EVERY MAN'S OPPORTUNITY.

If one is not faithful in an insignificant sphere he will not be faithful in a resounding sphere. If Peter will not help the cripple at the gate of the temple, he will never be able to preach three thousand souls into the kingdom at the Pentecost. If Paul will [304]not take pains to instruct in the way of salvation the jailor of the Philippian dungeon, he will never make Felix tremble. He who is not faithful in a skirmish would not be faithful in an Armageddon. The fact is we are all placed in just the position in which we can most grandly serve God; and we ought not to be chiefly thoughtful about some sphere of usefulness which we may after a while gain, but the all-absorbing question with you and with me ought to be: "Lord, what wilt thou have me now and here to do?"

WHAT A HOME IS.

There is one word in my text around which the most of our thoughts will this morning revolve. That word is "Home." Ask ten different men the meaning of that word, and they will give you ten different definitions. To one it means love at the hearth, it means plenty at the table, industry at the workstand, intelligence at the books, devotion at the altar. To him it means a greeting at the door and a smile at the chair. Peace hovering like wings. Joy clapping its hands with laughter. Life a tranquil lake. Pillowed on the ripples sleep the shadows.

Ask another man what home is, and he will tell you it is want, looking out of a cheerless firegrate, kneading hunger in an [305]empty bread tray. The damp air shivering with curses. No Bible on the shelf. Children robbers and murderers in embryo. Obscene songs their lullaby. Every face a picture of ruin. Want in the background and sin staring from the front. No Sabbath wave rolling over that door-sill. Vestibule of the pit. Shadow of infernal walls. Furnace for forging everlasting chains. Faggots for an unending funeral pile. Awful word! It is spelled with curses, it weeps with ruin, it chokes with woe, it sweats with the death agony of despair.

The word "Home" in the one case means everything bright. The word "Home" in the other case means everything terrific.

I shall speak to you this morning of home as a test of character, home as a refuge, home as a political safeguard, home as a school, and home as a type of heaven.

And in the first place I remark, that home is a powerful test of character. The disposition in public may be in gay costume, while in private it is in dishabille. As play actors may appear in one way on the stage, and may appear in another way behind the scenes, so private character may be very different from public character. Private character is often public character turned wrong side out. A man may receive you into his parlor as though he were a distillation [306]of smiles, and yet his heart may be a swamp of nettles. There are business men who all day long are mild, and courteous, and genial, and good-natured in commercial life, damming back their irritability, and their petulance, and their discontent; but at nightfall the dam breaks, and scolding pours forth in floods and freshets.

HOME MANNERS.

Reputation is only the shadow of character, and a very small house sometimes will cast a very long shadow. The lips may seem to drop with myrrh and cassia, and the disposition to be as bright and warm as a sheaf of sunbeams, and yet they may only be a magnificent show window to a wretched stock of goods. There is many a man who is affable in public life and amid commercial spheres who, in a cowardly way, takes his anger and his petulance home, and drops them on the domestic circle.

The reason men do not display their bad temper in public is because they do not want to be knocked down. There are men who hide their petulance and their irritability just for the same reason that they do not let their notes go to protest. It does not pay. Or for the same reason that they do not want a man in their stock company to sell his stock at less than the right price, lest it depreciate the value. As at some time [307]the wind rises, so after a sunshiny day there may be a tempestuous night. There are people who in public act the philanthropist, who at home act the Nero, with respect to their slippers and their gown.

AUDUBON'S GREATNESS.

Audubon, the great ornithologist, with gun and pencil, went through the forests of America to bring down and to sketch the beautiful birds, and after years of toil and exposure completed his manuscript, and put it in a trunk in Philadelphia for a few days of recreation and rest, and came back and found that the rats had utterly destroyed the manuscript; but without any discomposure and without any fret or bad temper, he again picked up his gun and pencil, and visited again all the great forests of America, and reproduced his immortal work. And yet there are people with the ten thousandth part of that loss who are utterly unreconcilable, who, at the loss of a pencil or an article of raiment will blow as long and sharp as a northeast storm.

Now, that man who is affable in public and who is irritable in private is making a fraudulent overissue of stock, and he is as bad as a bank that might have four or five hundred thousand dollars of bills in circulation with no specie in the vault. Let us learn to show piety at home. If we have it [308]not there, we have it not anywhere. If we have not genuine grace in the family circle, all our outward and public plausibility merely springs from a fear of the world or from the slimy, putrid pool of our own selfishness. I tell you the home is a mighty test of character! What you are at home you are everywhere, whether you demonstrate it or not.

HOME A REFUGE.

Again, I remark that home is a refuge. Life is the United States army on the national road to Mexico, a long march, with ever and anon a skirmish and a battle. At eventide we pitch our tent and stack the arms, we hang up the war cap and lay our head on the knapsack, we sleep until the morning bugle calls us to marching and action. How pleasant it is to rehearse the victories and the surprises, and the attacks of the day, seated by the still camp-fire of the home circle!

Yea, life is a stormy sea. With shivered masts, and torn sails, and hulk aleak, we put in at the harbor of home. Blessed harbor! There we go for repairs in the dry dock of quiet life. The candle in the window is to the toiling man the lighthouse guiding him into port. Children go forth to meet their fathers as pilots at the "Narrows" take the hand of ships. The [309]door-sill of the home is the wharf where heavy life is unladen.

There is the place where we may talk of what we have done without being charged with self adulation. There is the place where we may lounge without being thought ungraceful. There is the place where we may express affection without being thought silly. There is the place where we may forget our annoyances, and exasperations, and troubles. Forlorn earth pilgrim! no home? Then die. That is better. The grave is brighter, and grander, and more glorious than this world with no tent for marchings, with no harbor from the storm, with no place of rest from this scene of greed, and gouge, and loss, and gain. God pity the man or the woman who has no home!

A POLITICAL SAFEGUARD.

Further, I remark that home is a political safeguard. The safety of the State must be built on the safety of the home. Why cannot France come to a placid republic? Ever and anon there is a threat of national capsize. France as a nation has not the right kind of a Christian home. The Christian hearthstone is the only corner-stone for a republic. The virtues cultured in the family circle are an absolute necessity for the State. If there be not enough moral principle to make the family adhere, there [310]will not be enough political principle to make the State adhere. "No home" means the Goths and Vandals, means the Nomads of Asia, means the Numideans of Africa, changing from place to place, according as the pasture happens to change. Confounded be all those Babels of iniquity which would overtower and destroy the home. The same storm that upsets the ship in which the family sails will sink the frigate of the constitution. Jails and penitentiaries and armies and navies are not our best defence. The door of the home is the best fortress. Household utensils are the best artillery, and the chimneys of our dwelling houses are the grandest monuments of safety and triumph. No home; no republic.

AS A SCHOOL.

Further, I remark, that home is a school. Old ground must be turned up with subsoil plough, and it must be harrowed and re-harrowed, and then the crop will not be as large as that of the new ground with less culture. Now youth and childhood are new ground, and all the influences thrown over their heart and life will come up in after life luxuriantly. Every time you have given a smile of approbation, all the good cheer of your life will come up again in the geniality of your children. And every ebullition of anger and every uncontrollable display of indignation will be fuel to their disposition twenty, [311]or thirty, or forty years from now—fuel for a bad fire a quarter of a century from this.

You praise the intelligence of your child too much sometimes when you think he is not aware of it, and you will see the result of it before ten years of age in his annoying affectations. You praise his beauty, supposing he is not large enough to understand what you say, and you will find him standing on a high chair before a flattering mirror. Words and deeds and example are the seed of character, and children are very apt to be the second edition of their parents. Abraham begat Isaac, so virtue is apt to go down in the ancestral line; but Herod begat Archelaus, so iniquity is transmitted. What vast responsibility comes upon parents in view of this subject!

Oh, make your home the brightest place on earth, if you would charm your children to the high path of virtue, and rectitude, and religion! Do not always turn the blinds the wrong way. Let the light which puts gold on the gentian and spots the pansy pour into your dwellings. Do not expect the little feet to keep step to a dead march. Do not cover up your walls with such pictures as West's "Death on a Pale Horse," or Tintoretto's "Massacre of the Innocents." Rather cover them, if you have pictures, with "The Hawking Party," and "The Mill by the Mountain Stream," and [312]"The Fox Hunt," and "The Children Amid Flowers," and "The Harvest Scene," and "The Saturday Night Marketing."

CHEERFUL HOMES.

Get you no hint of cheerfulness from grasshopper's leap, and lamb's frisk, and quail's whistle, and garrulous streamlet, which from the rock at the mountain-top clear down to the meadow ferns under the shadow of the steep, comes looking for the steepest place to leap off at, and talking just to hear itself talk? If all the skies hurtled with tempest and everlasting storm wandered over the sea, and every mountain stream went raving mad, frothing at the mouth with mud foam, and there were nothing but simooms blowing among the hills, and there were neither lark's carol nor humming bird's trill, nor waterfall's dash, but only a bear's bark, and panther's scream, and wolf's howl, then you might well gather into your homes only the shadows. But when God has strewn the earth and the heavens with beauty and with gladness, let us take into our home circle all innocent hilarity, all brightness, and all good cheer. A dark home makes bad boys and bad girls in preparation for bad men and bad women.

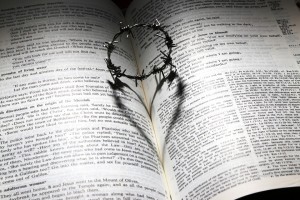

Above all, my friends, take into your homes Christian principle. Can it be that [313]in any of the comfortable homes of my congregation the voice of prayer is never lifted? What! No supplication at night for protection? What! No thanksgiving in the morning for care? How, my brother, my sister, will you answer God in the Day of Judgment, with reference to your children? It is a plain question and therefore I ask it. In the tenth chapter of Jeremiah God says He will pour out His fury upon the families that call not upon His name. O parents! when you are dead and gone, and the moss is covering the inscription of the tombstones will your children look back and think of father and mother at family prayer? Will they take the old family Bible and open it and see the mark of tears of contrition and tears of consoling promise wept by eyes long before gone out into darkness?

CHILDREN'S CURSES.

Oh, if you do not inculcate Christian principle in the hearts of your children, and you do not warn them against evil, and you do not invite them to holiness and to God, and they wander on into dissipation and into infidelity, and at last make shipwreck of their immortal soul, on their deathbed and in their Day of Judgment they will curse you! Seated by the register or the stove, what if on the wall should come out the history of your children? What a [314]history—the mortal and immortal life of your loved ones! Every parent is writing the history of his child. He is writing it, composing it into a song, or turning it into a groan.

My mind runs back to one of the best of early homes. Prayer, like a roof, over it. Peace, like an atmosphere, in it. Parents, personifications of faith in trial and comfort in darkness. The two pillars of that earthly home long ago crumbled to dust. But shall I ever forget that early home? Yes, when the flower forgets the sun that warms it. Yes, when the mariner forgets the star that guided him. Yes, when love has gone out on the heart's altar and memory has emptied its urn into forgetfulness. Then, the home of my childhood, I will forget thee! The family altar of a father's importunity and a mother's tenderness, the voices of affection, the funerals of our dead father and mother with interlocked arms like intertwining branches of trees making a perpetual arbor of love, and peace, and kindness—then I will forget them—then and only then. You know, my brother, that a hundred times you have been kept out of sin by the memory of such a scene as I have been describing. You have often had raging temptations, but you know what has held you with supernatural grasp. I tell you a man who has had such a good home as that never gets over it, and a man who has had a bad early home never gets over it.

[315]Again, I remark, that home is a type of heaven. To bring us to that home Christ left His home. Far up and far back in the history of heaven there came a period when its most illustrious citizen was about to absent Himself. He was not going to sail from beach to beach; we have often done that. He was not going to put out from one hemisphere to another hemisphere; many of us have done that. But he was to sail from world to world, the spaces unexplored and the immensities untraveled. No world had ever hailed heaven, and so far as we know heaven had never hailed any other world. I think that the windows and the balconies were thronged, and that the pearline beach was crowded with those who had come to see Him sail out the harbor of light into the oceans beyond.

THE EXILE.

Out, and out, and out, and on, and on, and on, and down, and down, and down He sped, until one night, with only one to greet Him, He arrived. His disembarkation so unpretending, so quiet, that it was not known on earth until the excitement in the cloud gave intimation that something grand and glorious had happened. Who comes there? From what port did He sail? Why was this the place of His destination? I question the shepherds, I question the camel drivers, I question the angels. I have found [316]out. He was an exile. But the world has had plenty of exiles—Abraham an exile from Ur of the Chaldees; John an exile from Ephesus; Kosciusko an exile from Poland; Mazzini an exile from Rome; Emmett an exile from Ireland; Victor Hugo an exile from France; Kossuth an exile from Hungary. But this one of whom I speak to-day had such resounding farewell and came into such chilling reception—for not even an hostler came out with his lantern to help Him in—that He is more to be celebrated than any other expatriated one of earth or heaven.

HOMESICKNESS.

It is ninety-five million miles from here to the sun, and all astronomers agree in saying that our solar system is only one of the small wheels of the great machinery of the universe, turning round some one great centre, the centre so far distant it is beyond all imagination and calculation; and if, as some think, that great centre in the distance is heaven, Christ came far from home when He came here. Have you ever thought of the homesickness of Christ? Some of you know what homesickness is, when you have been only a few weeks absent from the domestic circle. Christ was thirty-three years away from home. Some of you feel homesickness when you are a hundred or a thousand miles away from the [317]domestic circle. Christ was more millions of miles away from home than you could calculate if all your life you did nothing but calculate. You know what it is to be homesick even amid pleasurable surroundings; but Christ slept in huts, and He was athirst, and He was ahungered, and He was on the way from being born in another man's barn to being buried in another man's grave. I have read how the Swiss, when they are far away from their native country, at the sound of their national air get so homesick that they fall into melancholy, and sometimes they die under the homesickness. But oh! the homesickness of Christ! Poverty homesickness for celestial riches! Persecution homesick for hosanna! Weariness homesick for rest! Homesick for angelic and archangelic companionship. Homesick to go out of the night, and the storm, and the world's execration, and all that homesickness suffered to get us home!

THE HOME-GATHERING.

At our best estate we are only pilgrims and strangers here. "Heaven is our home." Death will never knock at the door of that mansion, and in all that country there is not a single grave. How glad parents are in holiday times to gather their children home again! But I have noticed that there is almost always a son or a daughter [318]absent—absent from home, perhaps absent from the country, perhaps absent from the world. Oh, how glad our Heavenly Father will be when He gets all His children home with Him in heaven! And how delightful it will be for brothers and sisters to meet after long separation! Once they parted at the door of the tomb; now they meet at the door of immortality. Once they saw only through a glass darkly; now it is face to face; corruption, incorruption; mortality, immortality. Where are now all their sins and sorrows and troubles? Overwhelmed in the Red Sea of Death while they passed through dry shod.

Gates of pearl, capstones of amethyst, thrones of dominion, do not stir my soul so much as the thought of home. Once there let earthly sorrows howl like storms and roll like seas. Home! Let thrones rot and empires wither! Home! Let the world die in earthquake struggle, and be buried amid procession of planets and dirge of spheres. Home! Let everlasting ages roll with irresistible sweep. Home! No sorrow, no crying, no tears, no death. But home, sweet home, home, beautiful home, everlasting home, home with each other, home with God.

A DREAM.

One night lying on my lounge, when very tired, my children all around about [319]me in full romp, and hilarity and laughter—on the lounge, half awake and half asleep, I dreamed this dream: I was in a far country. It was not Persia, although more than Oriental luxuriance crowned the cities. It was not the tropics, although more than tropical fruitfulness filled the gardens. It was not Italy, although more than Italian softness filled the air. And I wandered around looking for thorns and nettles, but I found that none of them grew there, and I saw the sun rise, and I watched to see it set, but it sank not. And I saw the people in holiday attire, and I said: "When will they put off this and put on workmen's garb, and again delve in the mine or swelter at the forge?" but they never put off the holiday attire.

And I wandered in the suburbs of the city to find the place where the dead sleep, and I looked all along the line of the beautiful hills, the place where the dead might most blissfully sleep, and I saw towers and castles, but not a mausoleum or a monument or a white slab could I see. And I went into the chapel of the great town, and I said: "Where do the poor worship, and where are the hard benches on which they sit?" And the answer was made me:

"WE HAVE NO POOR

in this country." And then I wandered [320]out to find the hovels of the destitute, and I found mansions of amber and ivory and gold; but not a tear could I see, not a sigh could I hear, and I was bewildered, and I sat down under the branches of a great tree, and I said: "Where am I? And whence comes all this scene?"

And then out from among the leaves, and up the flowery paths, and across the bright streams there came a beautiful group, thronging all about me, and as I saw them come I thought I knew their step, and as they shouted I thought I knew their voices; but then they were so gloriously arrayed in apparel such as I had never before witnessed that I bowed as stranger to stranger. But when again they clapped their hands and shouted "Welcome, welcome!" the mystery all vanished, and I found that time had gone and eternity had come, and we were all together again in our new home in heaven. And I looked around, and I said; "Are we all here?" and the voices of many generations responded "All here!" And while tears of gladness were raining down our cheeks, and the branches of the Lebanon cedars were clapping their hands, and the towers of the great city were chiming their welcome, we all together began to leap and shout and sing: "Home, home, home, home!"