- The Curtain Lifted

- WINTER NIGHTS

- THE POWER OF CLOTHES

- AFTER MIDNIGHT

- THE INDISCRIMINATE DANCE

- THE MASSACRE BY NEEDLE AND SEWING-MACHINE

- PICTURES IN THE STOCK GALLERY

- LEPROUS NEWSPAPERS

- THE FATAL TEN-STRIKE

- SOME OF THE CLUB-HOUSES

- FLASK, BOTTLE, AND DEMIJOHN

- THE HOUSE OF BLACKNESS OF DARKNESS

- THE GUN THAT KICKS OVER THE MAN WHO SHOOTS IT OFF

- LIES: WHITE AND BLACK

- A GOOD TIME COMING

[NOTE.—This chapter, in its first shape, was given some currency under the title of “The Evil Beast.” I have, however, so revised and added to that Lecture, that, as here given, it is essentially a new presentation of the dreadful Abomination of Rum, and it is in this present shape that I wish the public to receive it as a full expression of my views thereon. T.D.W.T.]

There has in all ages and climes been a tendency to the improper use of stimulants. Noah, as if disgusted with the prevalence of water in his time, took to strong drink. By this vice Alexander the Conqueror was conquered. The Romans, at their feasts, fell off their seats with intoxication. Four hundred millions of our race are opium-eaters. India, Turkey, and China have groaned with the desolation; and by it have been quenched such lights as Haller and De Quincey. One hundred millions are the victims of the betel-nut, which has specially accursed the East Indies. Three hundred millions chew hashish, and Persia, Brazil, and Africa suffer the delirium. The Tartars employ murowa; the Mexicans the agave; the people of Guarapo an intoxicating quality taken from sugar-cane; while a great multitude, that no man can number, are the disciples of alcohol. To it they bow. In its trenches they fall. In its awful prison they are incarcerated. On its ghastly holocaust they burn.

Could the muster-roll of this great army be called, and they could come up from the dead, what eye could endure the reeking, festering putrefaction and beastliness! What heart could endure the groans of agony!

Drunkenness: Does it not jingle the burglar's key? Does it not whet the assassin's knife? Does it not cock the highwayman's pistol? Does it not wave the incendiary's torch? Has it not sent the physician reeling into the sick-room; and the minister, with his tongue thick, into the pulpit? Did not an exquisite poet, from the very height of reputation, fall, a gibbering sot, into the gutter, on his way to be married to one of the fairest daughters of New England, and at the very hour when the bride was decking herself for the altar; and did he not die of delirium tremens, almost unattended, in a New York hotel? Tamerlane asked for one hundred and sixty thousand skulls, with which to build a pyramid to his own honor. He got the skulls, and built the pyramid. But if the bones of all those who have fallen as a prey to dissipation could be piled up, it would make a monster pyramid. Talk not of Waterloo and Austerlitz, for they were not fields of blood compared with this great Golgotha.

Who will gird himself for the journey, and try with me to scale this mountain of the dead—going up miles high on human carcasses, to find still other peaks far above, mountain above mountain, white with the bleached bones of drunkards!

Hang not your head or shut your eyes until we have seen it. We must get a sight at the monster before we can shoot him.

I will begin at our national and State capitals. Like government, like people. Henry VIII. blasts all England with his example of uncleanness. Catharine of Russia drags down a whole empire with her nefarious behavior. No Christian man can be indifferent to what every hour of every day goes on at Washington. While the Presidential Impeachment trial advanced, some of the men who were to render their solemn verdict on the subject were reeling in and out of the Senate chamber,—the intoxicated representatives of a free Christian people. It was a great question whether several members of that high court could be got sober in time to vote.

Only recently a Senator from New England rises up with tongue so thick, and with utterance so nonsensical, that he is led into the anteroom. He was a good "Republican."

One of the Middle States has a representative who very rarely appears in his seat, for the reason that he is so great an inebriate that he can neither walk nor ride. He is a good Democrat.

As God looks down on our State and national legislatures, he holds us responsible. We cast the votes. We lift up the legislators.

Will the time never come when this nation shall rise up higher than partisanship, and cast its suffrage for sober men?

The fact is that the two millions of dollars which the liquor dealers raised for the purpose of swaying State and national legislation has done its work, and the nation is debauched. Higher than legislatures or the Congress of the United States is the Whiskey Ring!

The Sabbath has been sacrificed to the rum traffic. To many of our people the best day of the week is the worst. Bakers must keep their shops closed on the Sabbath. It is dangerous to have loaves of bread going out on Sunday. The shoe-store is closed; severe penalty will attack the man who sells boots on the Sabbath. But down with the window-shutters of the grog shops. Our laws shall confer particular honors upon the rum traffickers. All other traders must stand aside for these. Let our citizens who have disgraced themselves by trading in clothing, and hosiery, and hardware, and lumber, and coal, take off their hats to the rum-seller, elected to particular honor. It is unsafe for any other class of men to be allowed license for Sunday work. But swing out your signs, oh ye traffickers in the peace of families, and in the souls of immortal men! Let the corks fly, and the beer foam, and the rum go tearing down the half-consumed throat of the inebriate. God does not see, does he? Judgment will never come, will it?

People say—"Let us have some law to correct this evil." We have more law now than we execute. In what city is there a mayoralty that dare do it? There is no advantage in having the law higher than public opinion. What would be the use of the Maine Law in New York? Neal Dow, the Mayor of Portland, came out with a posse and threw the rum of the city into the street. From the alms-house a woman came out and said, "Oh! if this had only been done ten years ago, my husband would not have died a drunkard, and I would not have been a widow in the almshouse."

But there are not enough police in the city of New York to stand by its Mayor in such an undertaking; public opinion is not educated.

I do not know but that God is determined to let drunkards triumph; and the husbands and sons of thousands of our best families be destroyed by this vice, in order that our people, amazed and indignant, may rise up and demand the extermination of this municipal crime.

There is a way of driving down the hoops of a barrel until the hoops break.

We are in this country, at this time, trying to regulate this evil by a tax on whiskey. You might as well try to regulate the Asiatic cholera, or the small-pox, by taxation. The men who distil liquors are, for the most part, unscrupulous; and the higher the tax, the more inducement to illicit distillation. New York produces forty thousand gallons of whiskey every twenty-four hours; and the most of it escapes the tax. The most vigilant officials fail to discover the cellars, and vaults, and sheds where this work is done.

Oh, the folly of trying to restrain an evil by government tariffs! If every gallon of whiskey made, if every flask of wine produced, should be taxed a thousand dollars, it would not be enough to pay for the tears it has wrung out of the eyes of widows and orphans, nor for the blood it has dashed on the altars of the Christian Church, nor for the catastrophe of the millions it has destroyed forever.

Oh! we are a Christian people! From Boston a ship sailed for Africa, with three missionaries, and twenty-two thousand gallons of New-England rum on board. Which will have the most effect: the missionaries, or the rum?

Rum is victor. Some time when you have leisure, just go down any of our streets, and count the number of drinking places. Here they are—first-class hotels. Marble floors. Counter polished. Fine picture hanging over the decanters. Cut glass. Silver water-coolers. Pictured punch-bowls. High-priced liquors. Customers pull off their gloves, and take up the glasses, and click them, and with immaculate pocket handkerchief wipe their mouth, and go up-stairs, or into the reading-room, and complete extensive bargains.

Here it is—the restaurant. All sorts of viands, but chiefly all styles of beverage. They who frequent this place have fairly started on the down grade. Having drunk once, they lounge at the corner of the bar until a friend comes up, and then the beverage is repeated. After a while they sit at the little table by the wall and order a rarer wine; for they feel richer now, and able to get almost anything. Towards bed-time they take out their watch and say they must go home. They start, but cannot stand straight. With a gentleman at each arm, they start up the street. More and more overcome, the man begins to whoop, and shout, and swear, and refuse to go any farther. Hat falls off. Hair gets over his eyes. Door-bell of fine house rings. Wife comes down the stairs. Daughters look over the banisters. Sobbing in the dark hall. Quick—shut the front door, for I do not want to look in. God help them!

Here it is—a wine-cellar. Going into the door are depraved men and lost women. Some stagger. All blaspheme. Men with rings in their ears instead of their nose; and blotches of breast-pin. Pictures on the wall cut out of the Police Gazette. A slush of beer on floor and counter. A pistol falls out of a ruffian's pocket. By the gas-light a knife flashes. Low songs. They banter, and jeer, and howl, and vomit. An awful goal, to which hundreds of people better than you have come.

All these different styles of drinking-places are multiplying. They smite a young man's vision at every turn. They pour the stench of their abomination on every wave of air.

I sketch two houses in this street. The first is bright as home can be. The father comes at nightfall, and the children run out to meet him. Luxuriant evening meal, gratulation, and sympathy, and laughter. Music in the parlor. Fine pictures on the wall. Costly books on the stand. Well-clad household. Plenty of everything to make home happy.

House the second. Piano sold yesterday by the sheriff. Wife's furs at pawnbroker's shop. Clock gone. Daughter's jewelry sold to get flour. Carpets gone off the floor. Daughters in faded and patched dresses. Wife sewing for the stores. Little child with an ugly wound on her face, struck in an angry blow. Deep shadow of wretchedness falling in every room. Doorbell rings. Little children hide. Daughters turn pale. Wife holds her breath. Blundering steps in the hall. Door opens. Fiend, brandishing his fist, cries—"Out! Out! What are you doing here!"

Did I call this house the second? No; it is the same house. Rum transformed it. Rum imbruted the man. Rum sold the shawl. Rum tore up the carpets. Rum shook its fist. Rum desolated the hearth. Rum changed that paradise into a hell!

I sketch two men that you know very well. The first graduated from one of our literary institutions. His father, mother, brothers and sisters were present to see him graduate. They heard the applauding thunders that greeted his speech. They saw the bouquets tossed to his feet. They saw the degree conferred and the diploma given. He never looked so well. Everybody said, "What a noble brow! What a fine eye! What graceful manners! What brilliant prospects!" All the world opens before him and cries, "Hurrah! Hurrah!"

Man the second. Lies in the station-house to-night. The doctor has just been sent for to bind up the gashes received in a fight. His hair is matted, and makes him look like a wild beast. His lip is bloody and cut.

Who is the battered and bruised wretch that was picked up by the police and carried in drunk, and foul, and bleeding? Did I call him man the second? He is man the first! Rum transformed him. Rum destroyed his prospects. Rum disappointed parental expectation. Rum withered those garlands of commencement-day. Rum cut his lip. Rum dashed out his manhood. RUM, accursed RUM!

This foul thing gives one swing to its scythe, and our best merchants fall; their stores are sold, and they slink into dishonored graves.

Again it swings its scythe, and some of our best physicians fall into sufferings that their wisest prescriptions cannot cure.

Again it swings its scythe, and ministers of the gospel fall from the heights of Zion with long-resounding crash of ruin and shame.

Some of your own household have already been shaken. Perhaps you can hardly admit it; but where was your son last night? Where was he Friday night? Where was he Thursday night? Wednesday night? Tuesday night? Monday night?

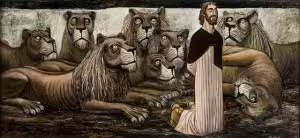

Nay, have not some of you, in your own bodies, felt the power of this habit? You think that you could stop? Are you sure you could? Go on a little further, and I am sure you cannot. I think, if some of you should try to break away, you would find a chain on the right wrist, and one on the left; one on the right foot, and another on the left. This serpent does not begin to hurt until it has wound around and round. Then it begins to tighten, and strangle, and crush until the bones crack, and the blood trickles, and the eyes start from their sockets, and the mangled wretch cries "O God! O God! Help! Help!" But it is too late; and nothing but the fires of woe can melt the chain when once it is fully fastened.

The child of a drunkard died. My friend, a minister of the Gospel, sat in a carriage with the drunkard, and the coffin of the little child. On the way to the grave, the drunkard put his hand on the lid of his child's coffin and swore that he never would drink again. Before the next morning had come he was dead drunk!

I spread out before you the starvation, the cruelty, the ghastliness, the woes, the terror, the anguish, the perdition of this evil, and then ask, Are you ready, fully and forever, to surrender our churches, our homes, our civilization, our glorious Christianity? One or the other must surrender. It can be no "drawn battle."

But how are we to contend?

First, by getting our children right on this subject. Let them grow up with an utter aversion to strong drink. Take care how you administer it even as medicine. If you find that they have a natural love for it, as some have, put in a glass of it some horrid stuff and make it utterly nauseous. Teach them as faithfully as you do the catechism, that rum is a fiend. Take them to the alms-house and show them the wreck and ruin it works. Walk with them into the homes that have been scourged by it. If a drunkard hath fallen into a ditch, take them right up where they can see his face, bruised, savage and swollen, and say, "Look, my son: Rum did that!"

Looking out of your window at some one who, intoxicated to madness, goes through the street, brandishing his fist, blaspheming God,—a howling, defying, shouting, reeling, raving and foaming maniac,—say to your son, "Look; that man was once a child like you." As you go by the grog-shop, let your boy know that that is the place where men are slain, and their wives made paupers, and their children slaves. Hold out to your children all warnings, all rewards, all counsels, lest in after days they break your heart, and curse your gray hairs.

A man laughed at my father for his scrupulous temperance principles, and said—"I am more liberal than you. I always give my children the sugar in the glass after we have been taking a drink."

Three of his sons have died drunkards; and the fourth is imbecile through intemperate habits.

Again, we will battle this evil at the ballot-box. How many men are there who can rise above the feelings of partisanship, and demand that our officials shall be sober men?

I maintain that the question of sobriety is higher than the question of availability; and that however eminent a man's services may be, if he have habits of intoxication, he is unfit for any office in the gift of a Christian people. Our laws will be no better than the men who make them.

Spend a few days at Harrisburg, or Albany, or Washington, and you will find out why, upon these subjects, it is impossible to get righteous enactments.

Again, we will war upon this evil by organized societies. The friends of the rum traffic have banded together; annually issue their circulars; raise fabulous sums of money to advance their interests; and by grips, pass-words, signs, and stratagems set at defiance public morals. Let us confront them with organizations just as secret, and, if need be, with grips, and pass-words, and signs maintain our position. There is no need that our philanthropic societies tell all their plans.

I am in favor of all lawful strategy in the carrying on of this conflict. I wish to God we could lay under the wine-casks a train, which, once ignited, would shake the earth with the explosion of this monstrous iniquity.

Again: we will try the power of the pledge. There are thousands of men who have been saved by putting their names to such a document. I know it is laughed at; but there are men who, having once promised a thing, do it. "Some have broken the pledge." Yes; they were liars. But all men are not liars. I do not say that it is the duty of all persons to make such signature; but I do say that it will be the salvation of many of you.

The glorious work of Theobald Mathew can never be estimated. At his hand four millions of people took the pledge, including eight prelates, and seven hundred of the Roman Catholic clergy. A multitude of them were faithful.

Dr. Justin Edwards said that ten thousand drunkards had been permanently reformed in five years.

Through the great Washingtonian movement in Ohio, sixty thousand took the pledge. In Pennsylvania, twenty-nine thousand. In Kentucky, thirty thousand, and multitudes in all parts of the land. Many of these had been habitual drunkards. One hundred and fifty thousand of them, it is estimated, were permanently reclaimed. Two of these men became foreign ministers; one a governor of a State; several were sent to Congress. Hartford reported six hundred reformed drunkards; Norwich, seventy-two; Fairfield, fifty; Sheffield, seventy-five. All over the land reformed men were received back into the churches that they had before disgraced; and households were re-established. All up and down the land there were gratulations, and praise to God. The pledge signed, to thousands has been the proclamation of emancipation.

I think that we are coming at last to treat inebriation as it ought to be treated, namely, as an awful disease, self-inflicted, to be sure, but nevertheless a disease. Once fastened upon a man, sermons will not cure him; temperance lectures will not eradicate the taste; religious tracts will not remove it; the Gospel of Christ will not arrest it. Once under the power of this awful thirst, the man is bound to go on; and if the foaming glass were on the other side of perdition, he would wade through the fires of hell to get it. A young man in prison had such a strong thirst for intoxicating liquors, that he cut off his hand at the wrist, called for a bowl of brandy in order to stop the bleeding, thrust his wrist into the bowl, and then drank the contents.

Stand not, when the thirst is on him, between a man and his cups! Clear the track for him! Away with the children: he would tread their life out! Away with the wife: he would dash her to death! Away with the Cross: he would run it down! Away with the Bible: he would tear it up for the winds! Away with heaven: he considers it worthless as a straw! "Give me the drink! Give it to me! Though hands of blood pass up the bowl, and the soul trembles over the pit,—the drink! give it to me! Though it be pale with tears; though the froth of everlasting anguish float in the foam—give it to me! I drink to my wife's woe; to my children's rags; to my eternal banishment from God, and hope, and heaven! Give it to me! the drink!"

Again: we will contend against these evils by trying to persuade the respectable classes of society to the banishment of alcoholic beverages. You who move in elegant and refined associations; you who drink the best liquors; you who never drink until you lose your balance: consider that you have, under God, in your power the redemption of this land from drunkenness. Empty your cellars and wine-closets of the beverage, and then come out and give us your hand, your vote, your prayers, your sympathies. Do that, and I will promise three things: First, That you will find unspeakable happiness in having done your duty; secondly, you will probably save somebody, perhaps your own child; thirdly, you will not, in your last hour, have a regret that you made the sacrifice, if sacrifice it be.

As long as you make drinking respectable, drinking customs will prevail; and the ploughshare of death, drawn by terrible disasters, will go on turning up this whole continent, from end to end, with the long, deep, awful furrow of drunkards' graves.

Oh, how this Rum Fiend would like to go and hang up a skeleton in your beautiful house, so that when you opened the front door to go in you would see it in the hall; and when you sit at your table you would see it hanging from the wall; and when you open your bed-room you would find it stretched upon your pillow; and waking at night you would feel its cold hand passing over your face and pinching at your heart!

There is no home so beautiful but it may be devastated by the awful curse. It throws its jargon into the sweetest harmony. What was it that silenced Sheridan's voice and shattered the golden sceptre with which he swayed parliaments and courts? What foul sprite turned the sweet rhythm of Robert Burns into a tuneless ballad? What brought down the majestic form of one who awed the American Senate with his eloquence, and after a while carried him home dead drunk from the office of Secretary of State? What was it that crippled the noble spirit of one of the heroes of the last war, until the other night, in a drunken fit, he reeled from the deck of a Western steamer and was drowned! There was one whose voice we all loved to hear. He was one of the most classic orators of the century. People wondered why a man of so pure a heart and so excellent a life should have such a sad countenance always. They knew not that his wife was a sot.

"Woe to him that giveth his neighbor drink!" If this curse was proclaimed about the comparatively harmless drinks of olden times, what condemnation must rest upon those who tempt their neighbors when intoxicating liquor means copperas, nux vomica, logwood, opium, sulphuric acid, vitriol, turpentine, and

strychnine! "Pure liquors:" pure destruction! Nearly all the genuine champagne made is taken by the courts of Europe. What we get is horrible swill!

I call upon woman for her influence in the matter. Many a man who had reformed and resolved on a life of sobriety has been pitched off into old habits by the delicate hand of her whom he was anxious to please.

Bishop Potter says that a young man who had been reformed sat at a table, and when the wine was passed to him refused to take it. A lady sitting at his side said, "Certainly you will not refuse to take a glass with me?" Again he refused. But when she had derided him for lack of manliness he took the glass and drank it. He took another and another; and putting his fist hard down on the table, said, "Now I drink until I die." In a few months his ruin was consummated.

I call upon those who are guilty of these indulgences to quit the path of death. O what a change it would make in your home! Do you see how everything there is being desolated! Would you not like to bring back joy to your wife's heart, and have your children come out to meet you with as much confidence as once they showed? Would you not like to rekindle the home lights that long ago were extinguished? It is not too late to change. It may not entirely obliterate from your soul the memory of wasted years and a ruined reputation, nor smooth out from anxious brows the wrinkles which trouble has ploughed. It may not call back unkind words uttered or rough deeds done—for perhaps in those awful moments you struck her! It may not take from your memory the bitter thoughts connected with some little grave: but it is not too late to save yourself and secure for God and your family the remainder of your fast-going life.

But perhaps you have not utterly gone astray. I may address one who may not have quite made up his mind. Let your better nature speak out. You take one side or the other in the war against drunkenness. Have you the courage to put your foot down right, and say to your companions and friends: "I will never drink intoxicating liquor in all my life, nor will I countenance the habit in others." Have nothing to do with strong drink. It has turned the earth into a place of skulls, and has stood opening the gate to a lost world to let in its victims, until now the door swings no more upon its hinges, but day and night stands wide open to let in the agonized procession of doomed men.

Do I address one whose regular work in life is to administer to this appetite? I beg you—get out of the business. If a woe be pronounced upon the man who gives his neighbor drink, how many woes must be hanging over the man who does this every day, and every hour of the day!

A philanthropist, going up to the counter of a grog-shop, as the proprietor was mixing a drink for a toper standing at the counter, said to the proprietor, "Can you tell me what your business is good for?" The proprietor, with an infernal laugh, said, "It fattens graveyards!"

God knows better than you do yourself the number of drinks you have poured out. You keep a list; but a more accurate list has been kept than yours. You may call it Burgundy, Bourbon, Cognac, Heidsick, Hock; God calls it strong drink. Whether you sell it in low oyster cellar or behind the polished counter of first-class hotel, the divine curse is upon you. I tell you plainly that you will meet your customers one day when there will be no counter between you. When your work is done on earth, and you enter the reward of your business, all the souls of the men whom you have destroyed will crowd around you and pour their bitterness into your cup. They will show you their wounds and say, "You made them;" and point to their unquenchable thirst, and say, "You kindled it;" and rattle their chain and say, "You forged it." Then their united groans will smite your ears; and with the hands out of which you once picked the sixpences and the dimes, they will push you off the verge of great precipices; while, rolling up from beneath, and breaking among the crags of death, will thunder:

"Woe to him that giveth his neighbor drink!"